History, Techniques and Recipes

Every single pilsener beer of today traces its roots back to a single point of origin in Pilsen, the Bohemian town where Josef Groll brewed the first pale lager in 1842. Every single pilsener beer in the world has been inspired, directly or indirectly, by that ur-beer. Even today, the name pilsner has so much admiration in the Czech Republic that only beers brewed in the town of Pilsen are allowed to be called pilsner (with one ‘e’). This respect can extend outside the borders as well, where many brewers in Germany and beyond will call their beer pilsener or pils, an appreciative nod to the Czech OG.

Because of this deference to the term “pilsner”, all sorts of terminology are used for Czech pilsner, and it can be confusing. When you see “Czech-style pilsner” on a label, it is pretty easy to understand what that means, as are Bohemian pilsner and BoPils. But none of those names are used in the Czech Republic. Instead, they call them světlý ležák and světlé speciální pivo, two types of beers that the BJCP has classified as Czech Premium Pale Lagers in the 3B section of the 2015 Guidelines. To keep things simple, I’ll be sticking with Czech pils or Bohemian pils in this article.

Czech style pilsners have a little more color and malt character in them than the German versions, primarily owing to the multiple decoctions in these beers. Czech grown Saazer-type hops are almost exclusively used in these beers; their spicy, herbal, floral, and subdued citrus notes are quite distinctive.

History

The town of Pilsen had been brewing beer for centuries. In the late 1830s, they ran into a particularly rough stretch, where the beer was so poor that 36 barrels of beer had to be dumped. They decided to build a modern brewery and hire a competent brewer. That brewer was a Bavarian named Josef Groll. Josef’s father owned a brewery in Bavaria where Josef had been experimenting with bottom fermenting (lager) beer. In October of 1842, Josef brewed the first batch of pale lager, which would become world-famous as Pilsner. With pale malt being a recent discovery, as it was during the British Industrial Revolution that the lighter kilning of malt was mastered, the circumstances lined up perfectly for Groll to invent a beer that would take the world by storm.

Pilsen’s lager became popular in nearby towns and sales began hitting German markets. German brewers, who are thought to have been making brown ales and lagers, quickly embraced and copied this new style themselves. The new beer from Pilsen continued to spread throughout the continent and eventually into America. Today, pilsener beer is the most popular type of beer in the world.

Pilsner Urquell

At the end of the 19th century, the original pilsner beer was trademarked under the name Pilsner Urquell. Urquell loosely means “the original well,” meaning the original source for the pilsner beer.

Today Pilsner Urquell is synonymous with quality and is a favorite of many drinkers, from the most casual to aficionados. Many brewers, professional and amatuer alike, have told me that their favorite beer has been an unfiltered pour of Urquell from the tanks at the source.

This fantastic video shows the three different ways you can pour Pilsner Urquell. It requires the use of a tap that is common throughout the Czech Republic and in parts of Germany, the side pull tap. Lukr creates the most well known and reputable version. Outside of Europe, you can buy them in the USA through Draft Choice. Warning: they are quite expensive!

Budweiser Budvar

This is the other recognizable name to most non-Czechs. Due to constant litigation with AB-InBev, the owners of the American Budweiser beer, this beer is known as Czechvar in the US. There have been over 100 official disputes involving these brands. This beer has become more like Pilsner Urquell in recent years. It’s a little less bitter and doesn’t pack that trademark wallop of honey that Urquell has, but drinking them side by side you will find quite a few similarities. Many consider it every bit as good as Pilsner Urquell, though people tend to have their clear favorite among the two.

Recipe Formulation

What you’re really going for in this beer is a glass that you can put up to your nose and get a nice whiff of bready malt, intertwined by a complex spicy and floral hop, with perhaps a hint of fruit from that hop. On the first sip, you’ll taste a rich, grainy, bready malt flavor, as well as an elevated, yet soft and smooth hop flavor. The full finish will remind you that you’re drinking a truly premium beer and leave you wanting more. Now let’s get into how to make it.

Malt

Bohemian pilsner malt is the star of the grist. Many brewers choose to use 100% Bohemian pilsner malt, and build up the malt’s richness using multiple decoctions in the mash (more on that later), which also helps achieve the style’s characteristic deep golden color. However, it’s not uncommon to see brewers using some Vienna or Munich malts in the grist, and a touch of caramel malt (such as carahell) can sometimes be found in recipes too. Nevertheless, you want to be careful about using too many specialty malts — it can create a beer that is not dry enough, that is too sweet and drinks too heavy.

As far as alternatives to Bohemian pilsner malt. I’ve known brewers that have preferred different base malts. For example, Weyerman’s Barke Pilsner malt, or their classic pilsner malt, are two fine choices to use if you prefer their flavor profiles over the Bohemian. While those are not Czech malts, they are widely-accepted substitutes for your Czech pils.

Water

The water in Pilsen is famously soft and allows brewers to use a higher amount of hops without the sharpness that you find in some other pilsners, like the Northern German version. Accordingly, the water profile for Bohemian pilsners should be very soft, almost devoid of mineral content. If your water isn’t soft enough to get close to the Pilsen profiles found in your recipe software, consider diluting your water with RO or distilled water to reduce the mineral levels.

Mashing

Decoction mashing is extremely common — many would even say a requirement — for a Bohemian pils. Two to three decoctions throughout the mash will help create some additional color to your beer, differentiating it from other pilsners, particularly German ones. You’ll also get some additional flavor complexity, with a subtle maltiness that decoction mashing can contribute. I recommend giving it a go for this style in particular. The most common way to achieve this is by taking out one-third of the mash volume, generally the thickest part, and boiling it for at least five minutes, then returning it back to the main mash to step it up to the next temperature. Repeating that two or three times will get you to where you want to be. Decoction mashing will also result in a more fermentable wort, which can help when using Czech yeast, which is lower attenuating compared to most German lager strains.

Many Bohemian malts are a little less modified than your typical base malt. Brewers find that a brief protein rest at or a few degrees above 122°F/50°C can help provide a fuller bodied beer. You can read a little more about the protein rest in How To Brew’s free online chapter. I usually target that protein rest before moving on to my typical Hochkurz mash, achieving the steps through 2-3 decoctions.

Hops

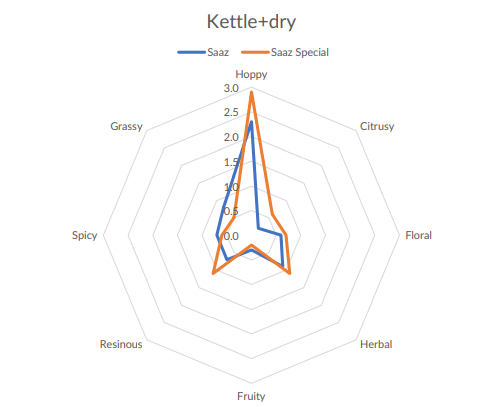

Saaz hops are pretty much the only generally accepted hop for this style. There are different variations of Saaz hops, but you want to look for ones that were grown in the Czech Republic. American Saaz is distinctly different, often a higher alpha acid and comes across a bit harsher than what you really want in this style beer. Czech Saaz will come across softer and with better overall flavor.

For hopping, 30-45 IBUs is common, with many of the award-winning homebrew and well regarded commercial recipes that I’ve seen online trending towards the middle to higher end of that range. Like in German pilsners, first wort hopping is common. Late boil hopping isn’t particularly common, though small amounts of hops towards the end of the boil are fine.

Quality

I’m a big proponent of using the best quality ingredients at your disposal. Czech pilsner is a beer that will not hide any corner-cutting from your design or technique. Access to premium quality Czech ingredients can be spotty, or even non-existent, in many parts of the world. I’d rather use fresh high quality German pilsner malt than older Bohemian pilsner malt. I’d rather use great smelling German Tettnanger hops in this style than older, less fragrant Czech Saaz. Just know that you’ll be moving away from the style with every substitution that you make. I think that’s fine, so long as you’re doing it for a good reason (quality). This is not the beer to make if you want to pinch pennies on ingredients. This should be your “Premium Lager” and you should treat it as such. Keep your $5/lb super deal Cascade hops in the freezer when making this beer!

Yeast

With yeast, the Czech lager yeasts are most common. Pilsner Urquell has used five different strains over the years, but since 1993 reportedly uses the H-strain. For Urquell, you’ll want to look at Wyeast 2001, White Labs WLP800, Imperial Organic Yeast L28, Omega Yeast Labs OYL-101, and Propagate Lab MIP-650 for the Urquell-H strain and Wyeast 2278 or Omega OYL-108 for the Urquell-D strain. Budvar origin yeast options would be Wyeast 2000 or WHite Labs WLP802. Wyeast says that the D strain will produce a very slightly less attenuated beer, with more malt character and less floral and fruity character, when compared to the H strain. The D strain may also throw some sulfur that will clean up during a diacetyl rest and is slightly more tolerant of higher temperatures.

Plenty of the traditional Czech beers have a sort of honeyed-note that borders on (or in some cases clearly is) diacetyl. The diacetyl is prominently present in Pilsner Urquell. I find the subtle honey note really attractive at low to medium serving temperatures, but I don’t attempt to replicate it when brewing. Chasing diacetyl is a dangerous game, and there is a thin line between a subtle and attractive honey character and off-putting butter bomb. It is incredibly difficult to target diacetyl levels in a professional setting, let alone for a home brewer.

Because of the diacetyl issue, I’ve seen plenty of brewers use the German lager yeast strain that they are most comfortable with instead of a Czech lager yeast. Czech lager yeast derives from German lager yeast, and they’re both meant to be quite clean and to let the malt and hops shine. Thus, I find this to be an acceptable substitution to make, particularly if you already have experience with a German lager strain. Just know that many German lager yeasts will attenuate a little bit more than the Czech equivalents, so you might want to adjust the malt bill to add a small touch of specialty malt to leave more body to the beer. Those malt adjustments can really help balance the additional dryness from those German yeasts.

Fermentation

Like most German lager yeasts, you’ll want to start fermentation in the mid 40s °F to low 50s °F (7°C-11°C). With the Czech yeasts, many people recommend a diacetyl rest of a few days around 60F. You can also patiently wait at your lower primary temperature until diacetyl clears, which is usually within 2-3 weeks from pitching. Next, long lagering at nearly freezing temperatures is common. At least three weeks in my experience, but up to six or even eight weeks is not unheard of. Some brewers feel that you experienced diminished returns as you get past 2-3 weeks, while others feel an extra few weeks is that last special touch that makes the beer special. My advice is to find out which side of that you land on and make it your standard cold lagering time for this beer.

Retool, Rebrew, Repeat, Master

If you follow the above tips, or one of the recipes below, you should be able to brew yourself a pretty darn good pilsner on your first try. However, there is a subtle balance in these beers that can take some time to really nail. Even if you brew the exact recipe below, the beer will taste a bit different on your system. Mashing times, fermentation temperatures, malt choices, different batches of Saaz hops and the timings you add; these are just a few of the adjustments that you can make from batch to batch and that will make it difficult to really dial in your beer consistently. It can be a lot of fun to brew these again and again, making minor tweaks and seeing the differences, getting closer and closer to the perfect pilsner.

Recipes

New Image Brewing Czech Pils

New Image is a brewery best known for it’s forward thinking IPAs. But across the style spectrum, their beers are of a high quality. In recent years the owner and head brewer, Brandon Capps, has really developed a passion for pilsner. His Czech Pils is a local favorite and he was happy to share the recipe with me. He recommends focusing heavily on your brewing process when brewing this style of beer. Take a look at the recipe notes for an array of tips.

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

100 min |

42.6 IBUs |

2.9 SRM |

1.049 |

1.011 |

4.9 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3 B |

1.044 - 1.06 |

1.013 - 1.017 |

30 - 45 |

3.5 - 6 |

2.3 - 2.7 |

4.2 - 5.8 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Barke Pilsner (Weyermann) |

9 lbs |

100 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Saaz |

3.5 oz |

70 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

3.3 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Saflager Lager (W-34/70) |

DCL/Fermentis |

80% |

48°F - 59°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Saccharification |

148°F |

75 min |

Saccharification |

156°F |

10 min |

Mash Step |

160°F |

10 min |

Mash Out |

170°F |

10 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

14 days |

49°F |

Secondary |

7 days |

49°F |

Aging |

35 days |

32°F |

Notes

| Brandon looks at this beer as more process driven than anything. He performs 2-3 decoctions to go from his 148F infusion to a 170F mashout. Each decoction lasts 10 minutes. He recommends knocking out as cold as possible down to 48F. Knockout with oxygen added and pitch the yeast into a holding vessel. Rest for several hours until a cold break has formed and some truble has settled. Rack the clearest portion into the fermentation vessel, leaving behind foam and bottom trub. The goal here is to eliminate bitter compounds trapped in the foam and dead yeast/trub from the bottom that can cause subtle off flavors. He holds at freezing for 3-8 weeks, with key indicators being turbidity and sulfur. When the beer drops brite and the H2S aroma/flavor has dissipated, the beer is ready to be finished. He recommends lagering under pressure, fining/filtering or otherwise removing as much yeast as possible to clear the beer and carbing it up nice and high at 2.8 volumes. |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Kupferschmidt Bohemian Pilsener

Jim Spaulding is a good friend of mine. He’s been on the Homebrewing podcast before to talk about his barn brewery, where he cranks out amazing European lagers. Jim runs the barn brewery the way that many people run a small farmhouse brewery. Its name comes from family lineage. Jim uses a pulley system to lift grain into the attic of his climate controlled brew-barn. The barn also houses his draft system, cold ingredient storage, a 4-person bar, cask pull, mini kitchen, full bathroom and lounge. There’s a small biergarten with a fountain out back. Jim crushes his grains up in the loft and then gravity feeds it to his brew system below, which contains a fantastic mash cooker. When Jim is finished brewing, he pumps his wort through a detachable hose and into a cellar under his house, where he conditions the beer in fermenters and uses heating pads to warm to temp. He brews seasonally, taking advantage of the cold winters to make the large number of lagers in his roster. Aside from a steam beer, he only brews traditional continental European beer.

The recipe that he provided is one that he has tinkered with over the years. He has really aimed to get that light honey note from Pilsner Urquell in this beer, as well as the right hopping. With each year’s batch, he’ll do multiple tastings comparing a fresh PU, Czechvar and his own beer, taking notes on similarities, differences and room for improvement in his recipe. I recently tasted the 2021 version, and it’s fantastic, his best yet. 2020 was not too shabby either! Below is the 2021 recipe, it’s noticeably more hop bitter-forward than the previous year, it really nails that honey note and it drinks incredibly well. Dare I say, his move from whole hop Saaz (unable to source stateside this year) to pellets might’ve been a great one?

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

60 min |

48.5 IBUs |

3.2 SRM |

1.049 |

1.013 |

4.7 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3 B |

1.044 - 1.06 |

1.013 - 1.017 |

30 - 45 |

3.5 - 6 |

2.3 - 2.7 |

4.2 - 5.8 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Bohemian Floor Malted Pilsner (Weyermann) |

5.5 lbs |

64.71 |

Vienna Malt (Weyermann) |

2.5 lbs |

29.41 |

Acidulated (Weyermann) |

8 oz |

5.88 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Saaz |

3 oz |

60 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

3.2 |

Saaz |

1.5 oz |

30 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

3.2 |

Saaz |

0.4 oz |

20 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

3.2 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Budvar Lager (2000) |

Wyeast Labs |

81% |

46°F - 56°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Protein Rest |

133°F |

10 min |

Mash Step |

144°F |

30 min |

Mash Step |

160°F |

40 min |

Mash Out |

170°F |

10 min |

Decoction |

203°F |

30 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

17 days |

48.5°F |

Secondary |

10 days |

48.5°F |

Aging |

60 days |

33°F |

Notes

| Note that Jim does a lesser known decoction style mashing procedure where he goes through all of his step mashes and then proceeds to simmer the entire mash for 30 minutes. For both the decoction temperature and hop utilization, keep in mind that this beer is brewed at roughly 5300 feet (1615m) in elevation. A sea level brewer's boil temperature will be higher and they will likely want to cut down the IBUs a little bit, perhaps down to the high 30s. Jim krausens his beer on day 17, under primary temperatures, and spunds them over a 7-14 day period to 15 PSI before slowly dropping to 33F for long lagering. Jim lagers his beers longer than almost anyone that I know, sometimes for 3-4 months. They tend to drink quite well for many months, I've had year old Pilsener that tastes far better than what you'd get from many professional breweries. That's both a testament to Jim's quality brewing skills and the large advantage of these beers never traveling further than from the beer line to the glass. |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Other Recipes

Here are some handpicked recipes for various Bohemian Pilsners online to give you an idea of some of the variation in ingredients and technique across the spectrum.

Free Access Recipes

Chodsko Pivo Bohemian Pilsner

This is an interesting recipe that showcases the malt variety that is common in these types of beers. It also uses Saaz Special hops, which are similar to the regular Saaz variety but with certain unique differences, and are approved for official use in Czech beers. Links to recipe.

Fox Farm’s Quiet Life Pilsner

Here is another recipe that is fairly straightforward, but distinguishes itself with some modest malt variety. Fox Farm Brewery is out of Connecticut Link to recipe.

Utopian Rebels Světlý Ležák

This 2018 London Brew Con Best of Show recipe comes from Rob Gallagher. It’s a wonderful looking recipe that features a triple decoction to achieve the malt character and complexity, as well as the classic Saaz hopping at three different points during the boil. Link to recipe.

Summer Session Pils

Grand Master Judge Josh Weikert published this recipe. It is a lower ABV (3.8%) and its use of biscuit malt in the grist really stands out as a unique choice. Link to recipe.

Hops and Berries Bohemian Pilsner

Hops and Berries was a homebrew shop in Fort Collins, Colorado that shuttered in recent years. The recipe has a good bit of Vienna malt in the grist, as well as an interesting choice in Sorachi Ace hops for bittering. Link to recipe.

Paid Access AHA

The following recipes can be accessed with an AHA Membership. The American Homebrewer’s Association is well worth the price of admission just for the Zymurgy Magazine and prior AHA Conference seminar content. On top of that, there are many 10-15% off discounts at participating breweries and homebrew shops across the country.

Czech Plz! What I Learned Brewing With the Czech Masters

Annie Johnson is the 2013 Homebrewer of the year and one of the most well known and respected people in the homebrewing world. Her 2017 Homebrew Con presentation on Czech beers contains a very high level approach to the beer. Link to recipe.

Chickity Czech Yourself Pilsner

This 2017 NHC Gold beer uses your typical Bohemian Pilsner malt and Saaz hops. It employs a very high single infusion mash to help produce more body in the final beer and shorter fermentation schedule with 34/70 that includes an extended diacetyl rest. Link to recipe.

Hobo BoHo Pils

This recipe is from Denny Conn and Drew Beechum’s Simple Brewing Book. It’s a great recipe for a classic Bohemian Pilsner with ingredients and techniques exactly as you’d expect. They list a few variations you can make on the base recipe as well. Link to recipe.

Meister Groll Bohemian Pils

This recipe comes from Jan Brücklmeier, a regular authoritative voice in the German Brewing Facebook Group and a professional brewmaster and brewery owner in his own right. The recipe may look similar to the last one at first glance, but the difference is in the technique. The decoction schedule is significantly different, and the hop additions are timed differently. If you made this beer and the last one, you would very likely see clear differences side by side. Link to recipe.

Other Content

The entire Czech pilsner chapter from Secrets of Master Brewers is shared online for free by the author, Jeff Alworth. Check it out here and then go buy the fantastic book. Jeff also did a short profile on a Bohemian Malster with some gorgeous photos here.

Evan Rail is another great resource if you want to learn more about this style, or anything Czech-beer related. He’s an American expat living in the Czech Republic and writing professionally about beer, travel and a number of other things. His articles on Good Beer Hunting in particular are worth a read.

One thought on “Deep Dive on Brewing Bohemian or Czech Style Pilsners”

Comments are closed.