Sourcing Quality Homebrew Ingredients Closer to Home

With pandemic related supply shortages and a shipping crisis taking place, there has never been a better time to source brewing ingredients from your own backyard. While these concerns may prove to be temporary, going local has longer lasting advantages too: lower shipping (energy) costs, freshness, the chance to find unique ingredients that might reflect your local “terroir”, and supporting your local economy.

I live in the United States and I’m familiar with the market, so my focus is on U.S.-based ingredients, but the principles of “brewing local” apply anywhere that brewing is big.

The U.S. is a massive country, and what is local in one part of the country isn’t considered local to another. The scale affects the supply chain. To give an idea of this scale, it’s possible to start in one corner of my home state of Colorado and drive across the state without even reaching the border on the other side! Contrast that to Europe, where an eight-hour overland journey can easily whisk you across multiple national borders. From Weyermann’s home in Bamberg, Germany, Weyermann malt can reach France in that eight hours!

Another contrast is that Europe has an array of traditional, high quality maltsters that many homebrewers are already familiar with. From Franco-Belges to Crisp and from Best Malz to Simpson’s. Conversely, North America, and the United States specifically, has undergone an ingredient supply transformation over the last half dozen years, going from a country where malt and hops were produced only at industrial scale, to a renaissance where local craft maltsters and hopyards are blossoming. That is the focus of this article.

(And sure, there are some smaller, lesser known maltsters in Europe and elsewhere, like maltsters in the Czech Republic, that I look forward to covering in future articles!)

Have Your Malt and Eat it Too

It used to be that as an American homebrewer, for certain styles of beer such as a Helles, you would have to source your ingredients from European suppliers or sacrifice quality. But today, there are a number of very high quality maltsters across the US, and specific heirloom variety grains being released from major maltsters too. New malting houses have sprung up in the U.S. over the last five years. In fact, in researching this article, I was surprised to learn that there are currently over thirty states in the U.S. that host at least one maltster! Let’s take a closer look at some of the standouts:

Admiral Maltings, California

When I tasted the American Pils collaboration from lager powerhouses Engren and Bierstadt Lagerhaus, I was pleasantly surprised at how much flavor was in the grain bill. Admiral’s floor-malted pils malt was absolutely fantastic and would have no problem in a glass next to anybody’s malt. They have a range of other interesting varieties that I’m excited to check out in the future.

Epiphany Craft Malt, North Carolina

I’ve had some tremendous beers from southeast boutique breweries such as Burial, Noda and Wooden Robot, and plenty of these beers were made with Epiphany’s malts. Their Foundation malt is in a lot of beers in the region, but they also offer a wide range of malts. The Smooth Operator black wheat malt looks particularly tasty.

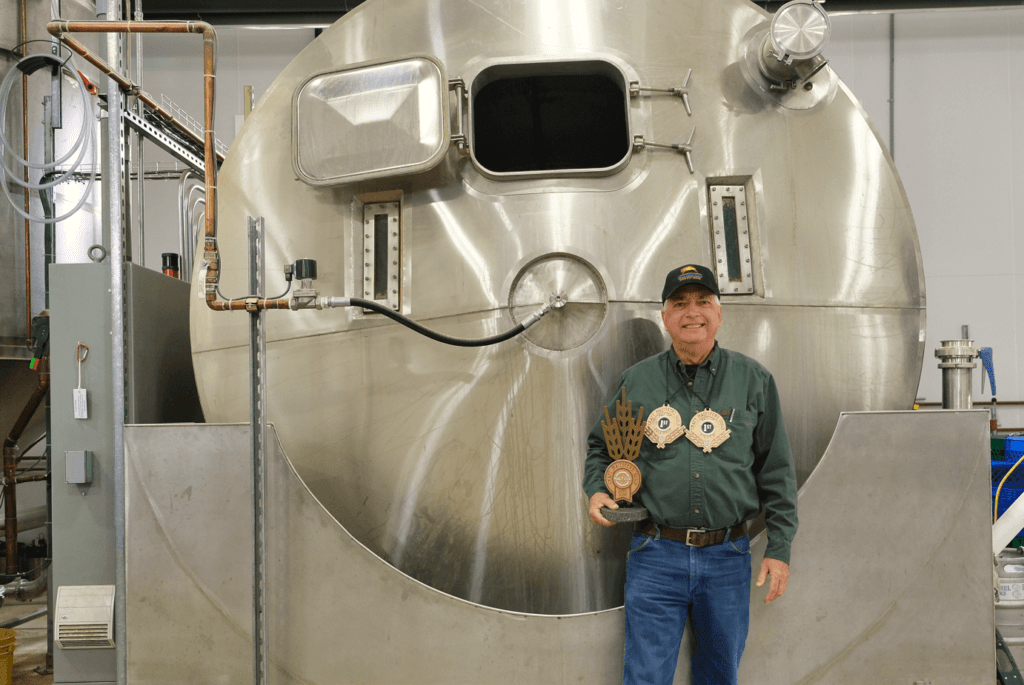

Gold Rush Malt, Oregon

Gold Rush won 1st place in both the Pale Malt and Pilsen Malt categories at the 2021 Malt Cup. They were the first to do so and it ensured them the overall Gold Award. While I haven’t used this malt, it’s now up there on my list to check out, maybe in a well balanced American amber. You can find this malt, as well as a few of the other Pacific-Northwest varieties, in the online homebrew store of FHSteinbart.

Mecca Grade Estate, Oregon

Perhaps best known in the homebrewing community for it’s frequent use by the Brulosophy crew, Mecca has an impeccable reputation among both homebrewers and quality breweries. I’ve heard time and again from brewers about how unique and delicious this malt is. Mecca also has a nice page on their website with homebrew recipes using their malts; that Nature of Reality Bock looks particularly delicious. Just as the Maris Otter varietal was developed in the U.K., Mecca Grade has worked with Oregon State University to develop the Full Pint barley varietal, which is the only varietal they grow. As Mecca Grade puts it. “Full Pint has an entirely unique, nutty, graham-cracker sweetness that is attributable to our farming practices, malting process, and yes, even terroir.”

Skagit Valley Malt, Washington

This Pacific Northwest standout has many different types of barley, from Czech style to purple! But what really jumps off the page is their Molasses Malt. It’s available in 25lb sacks to boot. Breweries as far south as Los Angeles regularly use their malt, and if brewers that far away are skipping plenty of quality maltsters in between, it must mean Skagit’s malt is of the highest quality.

Sugar Creek Malt, Indiana

I’ve heard a lot of fuss about Sugar Creek around the brewing community, particularly in smoked-beer circles. The Indiana maltster has over 40 different wood/barrel/herb/peat smoked malt choices to choose from! They have everything from traditional Beech to Indiana Peat, to Jamaican Pimento (said to impart intensely sweet and spicy notes). There is even a Tabasco barrel option. Sugar Creek has also received some attention for their Nordic inspired malts, particularly their Lambic Wind Malt. This is floor germinated grain that is dried by the sun and wind. It is used in, you guessed it, traditional Lambic beer. But it could also be used in traditional Gose or Berliner Weisse. Along with that Wind Malt, they have London Diastatic Brown Malt, based on the original malt that was used to make early porter beer in the UK. That sounds like the perfect malt to purchase, and then dive into Ron Pattinson’s historical beer website for recipe inspiration.

Troubadour Maltings, Colorado

This maltster is local to me, being only about one hour north of my home, and plenty of local breweries have used Troubadour in recent years. One brewer that really comes to mind is the newly opened Cohesion Brewery. Located in North Denver, Cohesion focuses solely on traditional Czech style lagers as well as the techniques that you typically find in those beers, such as multi-decoction mashes and horizontal lagering. Troubadour supplies Cohesion with a custom, undermodified pilsner malt, similar to the types of malts that you would see smaller Czech and German breweries using. These malts lend themselves to multi-step and decoction mashes and they give brewers a little more control over the final malt flavor. Troubadour offers a handful of malts to consumers, such as a pilsner malt that they apply maillard reactions to, the goal being to increase the fruit flavors of the malt.

Other Maltsters

To see what options may be close to where you live, take a look at the map below. If your local homebrew shop doesn’t carry the malt, consider contacting the maltster directly, they will often sell you a 50-55lb bag at a good price.

https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1YGTsgXqzkAzZVlJHKxhpZVUxbg7rQLq9

A Yeast Revolution

When I started home brewing, there were two American yeast choices: Wyeast and White Labs. Most brew stores seemed to stock maybe a dozen unique offerings between the two. Active dry yeast was still suspect, a carryover from the 1980-90s when quality control and reliable information were somewhat lacking. Fast forward to the present, and there are dozens of yeast labs, pushing new products and quality controls in this industry. And the quality control of these labs is considered quite high, evidenced by the thousands of professional breweries using them. I’m going to explore some of the most innovative and reputable labs below, highlighting some of their unique and interesting offerings.

Bootleg Biology, Tennessee

I first heard about Bootleg Biology when a friend bought one of their backyard yeast wrangling kits a few years back. They popped up again when Colter gave me one of their Oslo kveik yeast packs last summer. The yeast makes a fantastic pseudo lager, clean as a whistle, and a crispness that can only really be achieved with 80%+ attenuation. All at fermentation temperatures in the 85°F/29°C range. They have a newer lager yeast called Regal. It is a blend of historic and modern lager yeast. What really stands out, is that the instructions tell you to start at lower lager temperatures, then raise it to around 85°F/29°. The result should be a high attenuating, clean beer that is produced in a fraction of the time that a traditional lager would take. I’m curious to try this one out in the near future. However, despite dipping their toes into the lager world,. Bootleg is best known and most sought after for their unique isolates and blends for making sour and funky beer, including the legendary Funkweapon series..

East Coast Yeast, New Jersey

Founded by the legendary Al Buck, East Coast Yeast is perhaps the first yeast lab to toss its hat into the ring to compete with Wyeast and White Labs, always distributing only through one local homebrew shop. ECY offers a lineup that comprises an almost entirely unique selection of yeast and when their yeast is made available for pre-order, it typically sells out within hours, even these many years later and despite the proliferation of other yeast labs.

Escarpment Labs, Canada

When writing my Brewing Clean Beer with Kveik Yeast article for Zymurgy last year, Richard Preiss, owner of Escarpment Labs, was a fantastic resource. He connected me to Canadian brewers using kveik in all sorts of pseudo lagers and answered numerous questions that I had. His KRISPY kveik yeast was tough to find in the US at the time, so when James at Lake Fork Brewing hooked me up with some on a visit to Colorado, I was really excited to try it out. It’s a fantastic clean kveik yeast that fermented very well in the 70°F/21°C range. It dried out nicely in my American Pilsner and even my biggest lager aficionado friends wanted a second pint from that tap. KRISPY was originally a part of Escarpment’s Kveik Ring, a monthly limited batch release of a new kveik strain. Another interesting strain from Escarpment is Jötunn, a saison strain bred with a kveik strain, achieving a flocculant yet diastatic combination. I’ve yet to try this one, but it’s on my short list.

GigaYeast, California

When GigaYeast’s Vermont IPA yeast came out years ago, it created a pretty big buzz. It was reportedly the Heady Topper strain, and the massive HomebrewTalk thread on cloning that beer was generally focused on Giga and Yeast Bay’s versions of that yeast. The Heady Topper clone thread continues to grow today, with almost 4,000 posts. More recently, Gigayeast continues that trend of hazy IPA yeasts with their British Haze yeast.

Inland Island, Colorado

Founded in 2014, Inland Island supplies a wide range of professional breweries across the United States. They’ve also made a deliberate push to have homebrew vials available in various shops as well. They have a very wide selection of yeast, including seven different saison strains, a few of which I’ve really enjoyed in homebrew club members’ saisons.

Imperial Organic Yeast, Oregon

Imperial Organic Yeast IOY), founded by former Wyeast staffers, was the pioneer, along with Omega Yeast Labs, to offer more than 100 million cells of yeast in a pack. Today, besides many of the mainstay strains offered by most labs, such as the Chico, Manchester, Conan, and Fuller’s strains, IOY is known for making wonderful blends and offering lager strains that are not readily available elsewhere, such as L17 Harvest, the Augustiner strains.

Maniacal Yeast, Maine

Maniacal is the only lab on this list that I haven’t personally used. But I’ve included them because they offer a very unique product: hop terpenes. Hop terpenes are being used by some of the most innovative IPA breweries in the US. They work really well at the end of the boil and in the dry hop and they’re very efficient at delivering a great deal of hop flavor. If you’re a subscriber to Beer and Brewing Magazine, you can see an article I wrote on hop terpenes in the August-September 2021 IPA issue. Aside from hop terpenes and one lesser known kveik yeast, Maniacal doesn’t seem to have much of anything listed on their website. I’d email them if you’re curious, as their website has always been a little behind most of the other companies listed in this article, particularly the yeast labs.

Omega Yeast, Illinois

Omega hails from Chicago, their offices are actually near where I lived in the early days of Chicago’s craft beer scene, when breweries like Revolution, Metropolitan and Half Acre were just getting started. Omega is probably best known for Lutra, likely the most popular lager-like kveik strain. Lutra is a clean isolate of Hornindal, a classic kveik strain known for it’s pleasant tropical notes and vigor. Both professional and homebrewers seem to split into two camps on how to ferment this yeast: Hot and very fast, or low and somewhat fast. And by low, I mean closer to 70°F/21°C. I’ve had both examples and I’m still undecided. The lower temperatures produce a cleaner product, but at the sacrifice of some attenuation. The higher temps produce a more well attenuated, but less clean beer. In my handful of beers using this yeast, I’ve had the best results with maltier lager recipes. But you can trump my own experience with the dozens of favorable posts per month over in the Kveik Facebook Group about making pale lager-like beer with Lutra.

Propagate Yeast, Colorado

This is my local lab and one I’ve used frequently over the last couple of years. Matthew Peetz co-founded Inland Island, but split off a few years ago to start Propagate. Today, they supply over 200 professional breweries. Their yeast is available locally in the Colorado market at homebrew shops, and you can order it out of state online. One of the most unique things about Propagate is that Matthew likes to keep his kveik strains, received directly from Lars Marius Garshol, preserved in their original state. That includes any bacteria that may be present. This gives them a more authentic feel. And I can personally attest to these strains brewing very good beer, from traditional Norwegian beer to clean pseudo lagers. Beyond that, Propagate offers a wide array of yeasts for all styles of beer.

The Yeast Bay, California

The Yeast Bay is unique in that their founder decided to focus on collecting, isolating, and testing strains, while leaving propagation to one of the big boys on a contract basis. This allowed TYB to quickly expand their lineup of unique strains. They were the first to offer the Conan strain (their Vermont Ale yeast), which paid the bills during the heady Heady Topper clone days. And It continues to be popular. The Yeast Bay now offers a diverse range of yeasts that suits the full range of beer styles. Their Franconian Dark Lager yeast looks particularly appealing to me. One really nice thing is that they have a page on their website dedicated to Award Winning Recipes using their yeast.

What About Active Dry Yeast?

While the global active dry yeast companies have substantially expanded their range of offerings in recent years, there haven’t really been any American upstarts as far as I know. What’s up with that? Active dry yeast offers advantages like ease of use, ease of storing, length of storing, space saving and better protection during shipping. I’d speculate that the equipment expense and expertise in active dry yeast is too great of a hurdle and that live cultures appeal much more to small upstarts. I asked Matthew Peetz of Propagate Yeast about this and he pretty much agreed with those two points, while adding a third: the price of dry yeast is 33-55% lower than liquid yeast, so you would be doing something more expensive and difficult for less money. Perhaps selling active dry yeast only works at industrial scale?

Update: As this article was being published, Omega announced a dry yeast version of their popular kveik strain Lutra. They’ve partnered with a major dry yeast producer for this version of Lutra. Hopefully we’ll see more of this in the future.

Hops Around the Country

While the Pacific Northwest has long been regarded as America’s Napa Valley of hops, hop fields across the U.S. have been revived over the years. This is due in part to the massive rise in small craft breweries across the U.S., the push to use local ingredients in beer and the attractiveness of pricing after some of the hop shortage seasons. Over in Germany you see a lot of citrus forward hop varieties being developed as well, owing to the greater demand for IPA type beers in one of, if not the most traditional beer markets in the world. One interesting component to all of this is that the difference in taste between the same hop varieties planted in different terroirs can be incredible. Below, I explore a few interesting regional hops that I’ve had experience with:

Hophead Farms, Michigan

Hophead is quite popular with professional breweries and they also act as a distributor for select European hops as well. But their Southwest Michigan grown hops are unique and fun. Years ago, I tried the Hophead Chinook variety in a smash pale ale. I was shocked at the citrus flavors, and lack of the trademark pine that is present in the Pacific Northwest version of the same hop. The Zuper Saazer is more than just a higher alpha version of Czech Saaz too. I’ve seen it used in everything from IPAs to hoppy lagers, it expresses itself far more boldly in both flavor and bitterness and it’s a lot of fun to use in beers where you want a little more kick from a noble-esque hop, without going full citrus. My fellow contributor, Chino Darji, has spoken to several hop producers in Minnesota and Michigan and used their hops, and he reports that the terroir in those states often results in citrus or tropical fruit presentation from hop varietals that are not known for it, and those small-scale farms often have the flexibility to adjust picking dates and drying schedules to enhance those unique characteristics.

New York Hop Guild

New York State was a dominant force in the production of hops in the 1800s. Unfortunately, hop disease forced production to move to more accommodating areas on the West Cost and in the Pacific Northwest. But New York has made a comeback in recent years. The Hop Guild offers some really fun New York varieties that I’ve enjoyed in Northeast region beers. They come in pretty big packs (11lbs), so talk to your local homebrew shop, or contact the Guild directly to see if you can get them in homebrew quantities. Hops grow wild in Central New York as a result of hop yards abandoned a century and a half ago, and with New York’s farm brewery statute, hop farms are having a resurgence midst massive demand for their products.

New Mexico Hops

About five years ago, Neomexicanus was all the rage. Found in the wild in New Mexico and previously difficult to obtain, this hop was used in everything from pale ales to saisons. A local grower here, Voss Farms, grew these and its flavor presented as orange, citrus and some light dank. A lot of local homebrewers bought rhizomes and still grow them to this day. In present time, you can find Neo grown across the country, from Yakima Valley to the east coast. If you’d really like to get into it full bore, consider staying in Santa Fe during the late summer and taking an adventure into the wild to find some of your own, like Jamie Bogner of Beer and Brewing did a few years ago.

Recipes

Alesong Brewing & Blending Brett Saison

In just over five years of operation, Eugen, Oregon’s Alesong has amassed quite an impressive collection of medals. Co-founder and brewmaster Matt Van Wyk has been really impressed with Mecca Grade Estate’s malt and they’re less than four hours away from the brewery. The Brett Saison is one of four core beers that Alesong uses to blend with. It’s a component of their award winning Touch of Brett series. If you wanted to make something closer to Touch of Brett, that beer is dry hopped to the tune of .75lb/bbl, or roughly 2oz/5gallons. The recipe below uses three different Mecca malts: the Pelton (pilsner) malt, Metolius (Munich) malt and Wickiup (red wheat) malt.

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

90 min |

24.7 IBUs |

4.3 SRM |

1.056 |

1.018 |

5.0 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

25 B |

1.048 - 1.065 |

1.002 - 1.008 |

20 - 35 |

5 - 22 |

2.8 - 3.5 |

3.5 - 9.5 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Pelton : Pilsner-style Barley Malt (Mecca Grade) |

6 lbs |

55.81 |

Wheat - White Malt |

1.75 lbs |

16.28 |

Oats, Flaked |

12 oz |

6.98 |

Wickiup : Red Wheat Malt (Mecca Grade) |

12 oz |

6.98 |

Metolius : Munich-style Barley Malt (Mecca Grade) |

8 oz |

4.65 |

Rye Malt |

8 oz |

4.65 |

Wheat, Torrified |

8 oz |

4.65 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Centennial |

0.13 oz |

90 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

10 |

Huell Melon |

0.5 oz |

10 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

7.2 |

Mosaic (HBC 369) |

1 oz |

30 min |

Aroma |

Pellet |

12.3 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Brettanomyces Bruxellensis (WLP650) |

White Labs |

95% |

65°F - 72°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Mash In |

158°F |

45 min |

Mash Out |

168°F |

10 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

21 days |

68°F |

Secondary |

0 days |

68°F |

Aging |

7 days |

33°F |

Notes

| The FG should be closer to 1.003 and ABV will be closer to 7%. The program isn't allowing me to manually adjust for the Brett yeast's high level of attenuation. The white wheat in the recipe is in place of Malpass wheat, which Matt uses (it's from a farm local to him). The hops in the recipe change depending on what he has in the cooler. Typically bittering charges are whatever is clean, and then two more additions of citrusy, fruity hops. Last batch he used Pacific Jade as hop additions 1&2 and then Wa-iti and Citra in the whirlpool. The original recipe had Magnum or Chinook in the boil and Amarillo and Citra as the next two additions. All this should do is encourage you to use what you have on hand and/or whatever sounds good to you. Matt usually adds a little bit of gypsum, since this is a hop accentuated saison. They usually put this beer into a barrel after chilling it. They then use it as a component and blend to taste with other beers. You can either bottle this beer up as-is after the chilling step on the fermentation schedule (make sure to carb it up nicely, at least 3 volumes as listed in the carbonation section), or you can put it in an oak barrel, on some lightly toasted oak cubes or spirals, then bottle it or even completely replicate Alesong's methods and use it as a component in a larger blend. |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Oskar Blues River Rhine Beach Party Kolsch

Juice Drapeau is the Head Brewer at Oskar Blue’s original Lyons, Colorado location. He met me at their Pearl Street bar in Boulder and we sipped a few River Rhines while talking about his approach to this beer. He pays special attention to his water, making custom additions for each of his beers. He suggests targeting a Cologne water profile for this beer. Juice loves using the local ingredients because of their freshness and high quality. The Troubadour Pils Malt and the Propagate Kolsch yeast have been great performers for him. He uses Akoya hops, a newer variety that adds some citrus to the classic spicy, herbal and floral character of noble hops.

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

60 min |

21.0 IBUs |

2.4 SRM |

1.044 |

1.007 |

4.9 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 B |

1.044 - 1.05 |

1.007 - 1.011 |

18 - 30 |

3.5 - 5 |

2.4 - 3.1 |

4.4 - 5.2 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Troubadour Pevec Pilsner Malt |

8 lbs |

100 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Akoya |

0.3 oz |

60 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

11.6 |

Akoya |

1 oz |

5 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

11.6 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Colorado Kolsch (MIP-511) |

Propagate Lab |

79% |

55°F - 65°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Mash In |

149°F |

75 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

10 days |

60°F |

Secondary |

4 days |

68°F |

Aging |

14 days |

33°F |

Notes

| The yeast is actually MIP 513 from Propagate. There was no entry for this in Beersmith, so I used another Propagate Kolsch yeast. But 513 is the yeast that Juice uses for Oskar Blues. 5.5 Mash ph Juice pays special attention to his water and has found a method that works well for his own system. Target a Cologne water profile. Colorado water is quite soft to begin with, so plenty of salt additions are made on this beer. Juice knocks out to 58F, let's the fermentation begin at 60F and allows the yeast to free rise to 68F. This keeps the yeast healthy and happy and let's it be expressive without being overly estery. |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Colorado Pils

This is my own recipe. I basically take my typical house German Pilsner beer, a Northern German Style Pilsner with a few late noble hop additions. I then replace the German malt with high quality local pilsner malt from Troubadour, my favorite hops (Hallertau) from Voss Farms and a German lager yeast from Propagate. Troubadour is an hour away and both Voss Farms and Propagate are less than 15 minutes away. With this recipe, you can substitute for your local ingredients. As long as you have high quality pilsner malt and noble-type hops to pair with an appropriate lager yeast, this should come out really tasty.

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5.2 gal |

70 min |

39.2 |

2.7 SRM |

1.048 |

1.009 |

5.12 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 D |

1.044 - 1.05 |

1.008 - 1.013 |

22 - 40 |

2 - 5 |

0 - 0 |

0 - 0 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Troubadour Pevec Pilsner Malt |

8.999 lbs |

100 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Voss Farms Hallertauer |

2 oz |

60 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

4.3 |

Voss Farms Hallertauer |

0.75 oz |

15 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

4.3 |

Voss Farms Hallertauer |

0.75 oz |

3 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

4.3 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Andechs Lager Yeast (MIP-620) |

Propagate Lab |

81% |

32°F - 32°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Saccharification |

144°F |

35 min |

Mash Step |

154°F |

35 min |

Mash Step |

160°F |

10 min |

Mash Out |

170.1°F |

10 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

14 days |

51.1°F |

Secondary |

4 days |

51.1°F |

Tertiary |

30 days |

39.9°F |

Aging |

0 days |

32°F |

Notes

| I usually ferment around 50-52F for first generation lager yeast. 10-14 days later once the beer has reached terminal gravity and diacetyl has cleared, I rack it into a keg and slowly lower over four days to 40F. I rest here for 5-7 days. I then lower to 33F and let it lager for around four weeks. Biofine towards the end and serve spritzy, 2.5-3 volumes of carbonation. I often pressure ferment these, 6-8 PSI during the primary and then ramp it up to near serving PSI range once it is done fermenting. I brew at around 5200 feet in elevation. You might want to adjust the hops down about 20% if you're brewing at sea level. 5.2 mash PH target, I use acidulated malt for this. Our water is soft here, not Pilsen soft, but it's pretty darn soft and very suitable. |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |