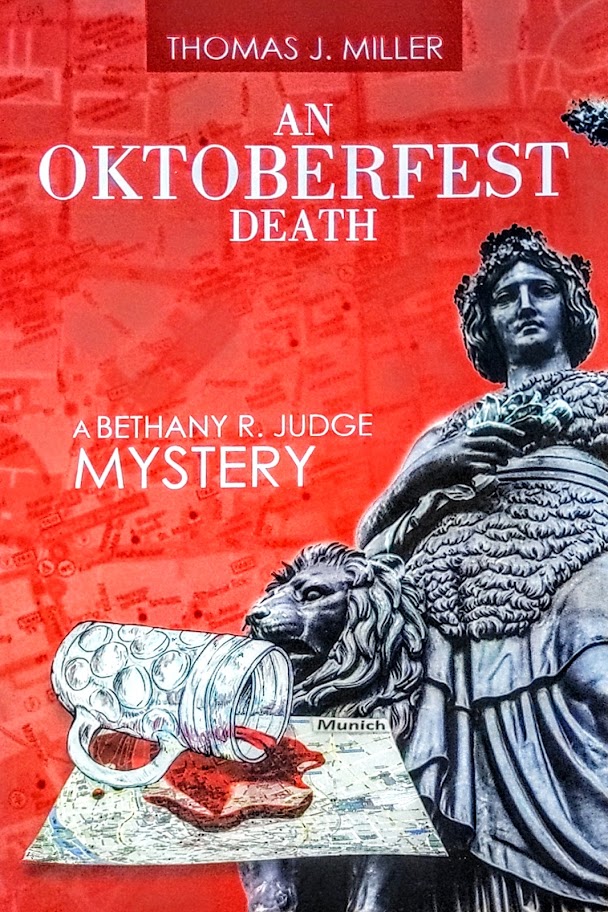

In my novel, “An Oktoberfest Death,” the fictional Master Cicerone Bethany R. Judge sets off on a journey to Munich in order to taste the highest quality Bavarian beers. During a stay that is soured by lots of death and international intrigue, Bethany still finds time to refine her palate with an overabundance of Helles, Dunkel, Hefeweizen, and Oktoberfest beers.

Funny thing, though, is that she never stumbled upon a Kellerbier.

After publishing the novel, I got to wondering what Bethany had missed out on during her misadventures in Munich and Garmisch, so I set off to make a Kellerbier that her refined palate would praise.

The Kellerbier style is not a style you hear about too much in the United States, but that does not mean it lacks a storied past. Beer historians tell us this style originated in the Franconia region of Germany, just to the north of Bavaria, with a background dating to the Middle Ages and the very start of lagering beer. Back in those days the concept of refrigeration was still several centuries away, so brewers would make beer in the cooler months and then store barrels inside cool caves. These caves served as natural cellars, allowing the beer to mature slowly at low temperatures.

Kellerbier is literally translated as “cellar beer” and speaks to the traditional technique noted above. On top of that, brewers learned to condition their beer in unsealed casks, which allowed carbon dioxide to escape out the bung hole. Only in the waning days of secondary fermentation would they seal the hole, allowing the beer to naturally carbonate in the barrel. Because it was unfiltered, the beer would have been cloudy from yeast, nutrients, and other brewing by-products.

That sounds a lot like the homebrewed beer we all make today!

A version of Kellerbier that has made its way into the American craft beer scene is Zwickelbier. Perhaps best illustrated in the craft beer scene by the St. Louis-based Urban Chestnut, traditional Zwickelbier tends to be younger, lighter, less hoppy, and more heavily carbonated thanks to the method of closing up the barrel bung near the end of primary fermentation.

The Beer Judge Certification Program classifies Kellerbier and its substyles as an Amber European Beer, though the modern version of the beer that has gained popularity outside of Franconia is more pale in color, similar to a Bavarian Helles. In brewing competitions it is possible to enter a pale version of a Kellerbier into the Amber European Beer category if the brewer specifically declares the entry is, in fact, pale.

Building an Award Winning Kellerbier

My “Summer 2021 Pale Kellerbier” won first place in the Amber European Beer category at the 2021 Indiana Brewers’ Cup, and earned me a coveted Blue Ribbon from the Indiana State Fair. The winning recipe was the result of some side-by-side brewing experimentations that employed different malt bills, slight variations in hopping techniques, and two different Imperial Yeast Bavarian lager strains. For the purpose of this article, I am sharing two of those experiments and their subsequent recipes.

It seems there are endless options when it comes to grain these days, but to get as authentic as possible for a Kellerbier you should look no further than German malt. The Kellerbier style made it interesting to experiment among the different grains available to homebrewers. In my different attempts, I went in search of the best base malts to accentuate the youthful characteristics intrinsic to the style. As you will note in the malt bills below, in these recipes and others I followed a strict percentage calculation for the malt bills of 86.27% for the Pilsner base malt, 10.59% for Vienna malt, and then always 1.57% of Best Malz Carahell and 1.57% Weyermann Acid malt. So, ultimately, I was searching for that perfect Pilsner malt/Vienna malt combination to create my Kellerbier.

For the two examples referenced in this article, in the first batch I used Weyermann Barke Pilsner (86.27%) malt blended with Weyermann Barke Vienna malt (10.59%), Best Malz Carahell (1.57%) and Weyermann Acid Malt (1.57%). Barke malt is malty and delicious, so I was pretty excited for the outcome. The Weyermann website says it best about this line of malts – “Barke brings with it the best conditions for an intense malt taste in the beer.” That proved more than true in this first recipe. The two largest malt additions produced a delicious beer, though the flavors tended to come across more robustly than the Kellerbier style demands, sending the beer down the path of a classic Bavarian Exportbier.

Forming the second malt bill were Best Malz German Pilsner malt (86.27%) blended with Avangard Vienna malt (10.59%), Best Malz Carahell (1.57%) and Weyermann Acid Malt (1.57%). The Best Malz website describes their Pilsner malt as giving “beer a fresh and rounded taste,” forming “an excellent ‘light’ and enzymatic rich foundation.” Combined with the light, biscuity characteristics from the slightly less robust Avangard Vienna malt, this malt bill yielded superior results for the Kellerbier style, with the resulting beer more sprightly, youthful, and “cellar-like” in its presentation to the palate.

When it comes to hops, there are every kind of varieties available to brewers these days, but tradition precludes a true Kellerbier from straying down the path of those varietals that are more akin to New World brewing. Instead, focus on noble hop varieties such as Tettnang or Hallertau, targeting IBUs between 20-35.

With my “Barke” heavy beer, I employed the “first wort hopping” technique by adding a small amount – 0.5 ounces – of Hallertau hops as the wort was being sparged. In this pre-boil status, the hops still release all of their important oils and resins, but by allowing the hops to steep in this fashion the oils can convert to more soluble compounds, providing them the opportunity to add superior hop complexity to the finished beer. Once full boil was achieved, I added 2.0 ounces of Hallertau pellets and boiled for 90 minutes. As a finishing touch during whirlpool, I put a small amount of homegrown and dried Hallertau leaf hops in a muslin bag and allowed them to steep for several minutes before removing. As a whole, this hopping schedule lent itself well to the Barke malts, giving deep backbone to a beer recipe that I will continue to develop for what I hope will become an award-winning Exportbier.

By contrast, the “Best Malz” recipe and ultimate award winner showcased a deceptively simple hopping schedule that married beautifully to the blend of malts highlighted above. The bittering addition of Hallertau pellets was boiled for 90 minutes, and then a small (0.5 ounces) batch of pellets was tossed into the kettle after chilling the wort to pitching temperature. The wort was then whirlpooled and given ten minutes for the cold break material to fall to the center of the brew kettle, at which time it was transferred to the fermenter and the yeast was pitched.

Imperial Yeast makes a great product. When it comes to knowing you have enough lager yeast to confidently pitch a five-gallon batch, there is no better alternative. In the “Barke” beer I employed Imperial L17 Harvest and for the “Best Malz” beer I used the Imperial L13 Global.

I fermented these batches side-by-side at 50 degrees for eight days, then increased the temperature to 56 degrees for three days, 60 degrees for two days, and 65 degrees for three days as a final diacetyl rest.

Admittedly, I have a soft spot for the L17 Harvest because that yeast originates, reportedly, from Munich’s Augustiner Brau. This historic and incredible Munich brewery is, by all accounts, the favorite of Munich’s residents and has a reputation that spans the world. But, more importantly, the Augustiner Brau plays an important role in my novel, “An Oktoberfest Death,” because workers at the brewery are suffering mysterious and untimely deaths, and our protagonist Bethany R. Judge gets caught up in the web of intrigue that threatens not only Munich but also the world. Bethany, sadly, is just in Munich to drink beer but, somehow, she just can’t stay out of trouble.

Augustiner Brau also happens to brew what many consider the pinnacle of Munich-style export lagers, Edelstoff. That makes the L17 yeast selection perfectly suited for the malt bill and hopping schedule of the “Barke” beer. L17 contributes outstanding flocculation characteristics with low sulfur and low diacetyl and was the final touch to make the “Barke” recipe far less of a Kellerbier, and much more of an Exportbier.

L13 Global, by contrast, comes from the world famous Weihenstephan brewery located just outside of Munich. The yeast is described on the Imperial website as being “the world’s most popular lager strain” known for producing “clean, bright and crispy lager beers with a very low ester profile.” As promising as that all sounds for the lager brewer, the L13 also comes with the caveat that it is “extremely powdery, so long lagering times or filtration is required for bright beer.”

But, as it turns out, that powdery characteristic is a boon for the Kellerbier brewer. Remember the origin of the beer, as described at the outset of this article? That, traditionally, Kellerbier was served unfiltered from the barrel? Do you think those beers were crystal clear, like today’s filtered lagers? Of course not! My experiment clearly demonstrated that the L13 Global yeast, when fermented carefully under controlled temperatures, was the clear winner for the Kellerbier style.

As a final note, before you even get to the malt bill or the hopping schedule or the yeast, you need to think about your water. After all, as the Bavarian Purity Law instructs us, beer should consist of only water, barley, hops, and yeast. And water is first on the list because beer is 90 to 95 percent water!

Sadly, most municipal water these days is pretty suspect when it comes to beer brewing. My approach is to get off on the right foot with Reverse Osmosis water, either by installing an R/O system at your residence or procuring the gallons needed for the batch size you plan to brew. At thirty-nine cents per gallon from my local grocery store, I choose the latter course of action.

Reverse Osmosis water lets you start with a clean slate. After that, when it comes to water and pH, I employ a Charlie Papazian mindset to my homebrewing, meaning I try to “relax, don’t worry, and have a homebrew.” In other words, I don’t get too bent out of shape about this whole part of the hobby.

For Kellerbier (and my “Barke” Exportbier), I made a simple addition of Calcium Chloride to support the beer characteristics for which I was shooting. Recommendations vary a bit, but I settled on 2.9 – 3.0 grams of CaCl2 into 8.5 gallons of R/O water. The acidulated malt is added into the malt bill to help lower the mash pH, but I considered it unnecessary to track pH during either brew session.

There is plenty of debate about whether German malts require step mashing, or if a single temperature infusion mash would suffice. That’s an experiment for another time, but for these two brews I held to some degree of tradition and put the step mash to work. You might consider a protein rest for 10-15 minutes at about 122 degrees if you fear your pilsner malt is undermodified, but I felt confident enough to avoid that step, instead mashing in for both batches to target a 10 minute mash recirculation at 140 degrees. This is the lowest end of alpha-amylase production within the brewers window, so the focus is upon good beta-amylase production and the front end of establishing strong fermentability characteristics. I also use this step for establishing the mash bed for recirculation.

After 10 minutes, tweak the temperature to 145 degrees for 20-25 minutes. Again, you are focusing on beta-amylase and fermentability, but are now starting to catch the attention of the alpha-amylase enzymes, in preparation of the next step.

After sitting at 145 degrees for 20-25 minutes, increase the mash temperature to 152 degrees. This is square in the center of the brewers window and exactly the point of intersection between the beta and alpha-amylase enzymes doing their work. Fermentability is on the decline during this stage of sugar production, while dextrin production is on the upswing. After 30 minutes at 152 degrees, bump the temperature to 162 degrees, allowing the alpha-amylase to complete their work, with the goal of a nice mouthfeel in the finished beer. The temperature climb from 152 to 162 degrees should take about ten minutes depending on your homebrewing setup, so there is not much need to hang at 162 degrees for more than a few extra minutes. After that, mash out at 170 degrees, sparge, and boil.

I have provided the recipes below for the two beers described above – the “Barke” Exportbier and the award winning “Best Malz” Kellerbier. While the brew day experiment was to chase down a Kellerbier recipe that would make Bethany R. Judge proud, the result was that I created an excellent foundation for future Exportbier batches and a Kellerbier that surpassed the competition!

For readers interested in my novel and others to come in the Bethany R. Judge series, you can visit my author website at www.thomasjmillerauthor.com. Signed copies of “An Oktoberfest Death” are now available. You can also click the hot links in the article to order a copy of the novel – in paperback or Kindle format – from Amazon.

Bethany’s Favorite Exportbier

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

90 min |

28.4 IBUs |

3.3 SRM |

1.050 |

1.013 |

4.8 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

7 C |

1.048 - 1.054 |

1.012 - 1.016 |

25 - 40 |

7 - 17 |

2.5 - 3 |

4.8 - 5.4 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Barke Pilsner (Weyermann) |

7.955 lbs |

86.27 |

Barke Vienna Malt (Weyermann) |

15.62 oz |

10.59 |

Acidulated (Weyermann) |

2.31 oz |

1.57 |

Carahell (Weyermann) |

2.31 oz |

1.57 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hallertauer Mittelfrueh |

0.5 oz |

90 min |

First Wort |

Pellet |

2.8 |

Hallertauer Mittelfrueh |

2 oz |

90 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

2.8 |

Hallertauer Mittelfrueh |

0.6 oz |

15 min |

Aroma |

Pellet |

2.8 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Harvest (L17) |

Imperial Yeast |

72% |

50°F - 60°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Protein Rest |

140°F |

10 min |

Saccharification |

145°F |

25 min |

Mash Step |

152°F |

30 min |

Mash Step |

162°F |

5 min |

Mash Out |

170°F |

10 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

8 days |

50°F |

Secondary |

7 days |

56°F |

Tertiary |

3 days |

32°F |

Aging |

28 days |

33°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Award Winning Pale Kellerbier

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

60 min |

28.7 IBUs |

3.4 SRM |

1.050 |

1.012 |

5.0 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

7 C |

1.048 - 1.054 |

1.012 - 1.016 |

25 - 40 |

7 - 17 |

2.5 - 3 |

4.8 - 5.4 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

BEST Pilsen Malt (BESTMALZ) |

7.91 lbs |

86.27 |

Vienna Malt (Avangard) |

15.53 oz |

10.59 |

Acidulated (Weyermann) |

2.3 oz |

1.57 |

Carahell (Weyermann) |

2.3 oz |

1.57 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hallertauer Mittelfrueh |

2 oz |

90 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

3.7 |

Hallertauer Mittelfrueh |

0.5 oz |

15 min |

Aroma |

Pellet |

3.7 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

Global (L13) |

Imperial Yeast |

75% |

46°F - 56°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Protein Rest |

140°F |

10 min |

Saccharification |

145°F |

25 min |

Mash Step |

152°F |

30 min |

Mash Step |

162°F |

5 min |

Mash Out |

170°F |

10 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

8 days |

50°F |

Secondary |

7 days |

56°F |

Tertiary |

3 days |

32°F |

Aging |

28 days |

33°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |