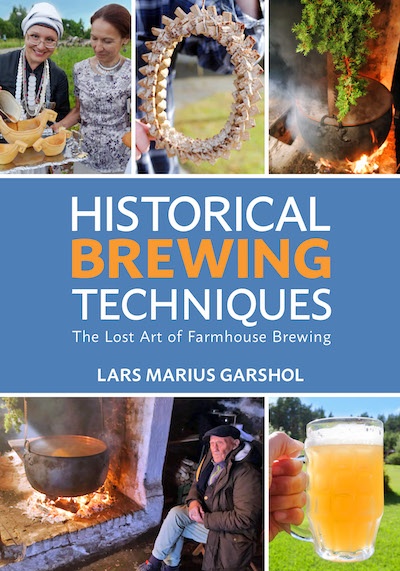

A few months ago I was lucky enough to get some time on the calendar and do an interview with Lars Garshol about historic brewing. He was in the final stages of releasing his new book. Historical Brewing Techniques (The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing). His book is out now and if you want to listen to our full interview you can listen to Episode 21 of the Homebrewing DIY Podcast. In talking to Lars I felt that there was so much more to learn. If you wanted to learn more I highly recommend reading his blog Lars Blog. You will find some great descriptions of his travels and how some of the European farmhouse brewers have made beers for hundreds of years, passed down through their families. So in this post here is some of our interview and his thoughts on historic farmhouse brewing!

Discovering Farmhouse Ales

Colter Wilson: How did you get into home brewing in general and, and how did you get started?

Lars Garshol: I actually never got into home brewing at all. I visit people to see how they Brew. I have brewed a couple of beers, but it’s only to test the recipes.

Colter Wilson: Your hobby is to travel and experience other people homebrewing, right?

Lars Garshol: Yes. Farmhouse brewers specifically. Yeah.

Colter Wilson So tell me about how you discovered farmhouse brewing and how that is turned into such a passion for you.

Lars Garshol: It started with, of all things, a book my wife gave me for Christmas, it was a Danish brewer and he wrote the book about how he was gonna create Nordic beers with Nordic flavors. He wanted to do it in the farmhouse brewing traditions for inspiration. And that was, that was the first time I got any real insight into it.

There was particularly one chapter that struck me about this Lithuanian farmer who malted his own barley, and they had the yeast in a jar well. And stuff like that. So I felt maybe Lithuania would be an interesting place to go. So I flew there, went to a bar, ordered a beer, and was flabbergasted because it was like no other beer really.

Colter Wilson: Well, what was the difference between that beer and the beer you had been drinking up until that point?

Lars Garshol: It’s totally different flavors. There’s this massive vivid straw flavor. Like you have a bale of hay, the bakes in the sun all day, and you’ve dropped face-first into it. It was really amazing. It was mainly the sense of mystery because it was so incredibly difficult to learn, basically anything at all.

It started right with that first beer. The bartender had recommended it to me, and when I tasted it, I ran straight back to the bar and I asked her. How did they make this flavor? Is it, is it the hops? She just looks at me. What is hops? This isn’t going to work. I’m not getting anywhere. And it’s been like that the whole way that. Normally, if you want to know about the some types of beers, you know, you read about that online or you find the book, you hear there was nothing, just a total black.

Colter Wilson: It’s like when you walk into someplace they have been doing the same thing for so long, it doesn’t need to be written down? They are like, this is beer. Is that the kind of mentality you ran into when you first started discovering these brewers?

Lars Garshol: Well, I took a long time to actually meet the people who make the beer. But yeah, that is the the way it works. Typically you learn to bew from your parents when you’re in school, and then eventually you start brewing for yourself and then you just know what to do.

Colter Wilson: Yeah. It’s like a cooking with your grandmother when you were a kid. Same idea. Right?

Lars Garshol: Yeah. That’s a very good comparison.

Colter Wilson: And then it’s the same traditions passed down, family to family, and the way that my family makes beer may not be exactly the same as somebody a few miles away makes beer. Is that correct?

Lars Garshol: Yeah, absolutely. I met one brewer and talk to him how he would brew, so he made raw ale. Then I drove on no 10 minutes, talk to another guy. He doesn’t boil the wort. That’s not going to be beer. Was the reaction from the other brewer.

Farmhouse Yeast

Colter Wilson: What other kinds of yeasts did you run into through your travels.

Lars Garshol: Quite a few Lithuanians who have their own farmhouse yeast. So some of those are homebrewers, but actually some are commercial farmhouse breweries in Lithuania. It’s also that some brewers still have their own yeast. We don’t really know how many. Then when I was in Russia. About 800 kilometers East of Moscow, it seems people there also have their own yeast and these are not Kveik. They have some similarities with Kveik in terms of their brewing properties, but genetically, they are not related to Kveik at all.

Colter Wilson: And some of those properties are things like tempeture resistance?

Lars Garshol: Yes, and also very fast fermentation. So, yeah, this is one thing we will cover in the book and are going to explain more. The normal pitch temperature and farmhouse brewing, whether you’re in central Russia or in the UK, is body temperature. they must have somehow. Oh, train their yeasts to handle this. They must have evolved to handle these temperatures, basically.

Colter Wilson: If you’re looking at hundreds of years and many thousands of generations of, of yeast, it does start to really hone into the environment it’s in right?

Lars Garshol: Yeah, that’s what’s happened. With the commercial beer yeasts that we know as well. They lived in commercial breweries for many centuries and adapted to the way the commercial breweries brew. So, in fact, the best temperature for the yeast to ferment is actually roughly body temperature. So it’s not really the farmhouse brewers that are strange. It’s the, it’s the commercial brewers that are strange.

Colter Wilson: So, and when you look at those farmhouse yeasts, they’re kind of symbiotic blends?

Lars Garshol: It is definitely a culture, there are many, many strains of yeast in those cultures. Whether there’s anything else varies a lot. Quite a few of these seem to be free of any contamination at all. At least that the the labs have been able to find, but in some cases, there is other stuff in there.

Colter Wilson: What are the different ways through your travels, that people stored these yeasts? For them to use in future batches?

Larsh Garshol: In Norway farmers in the South generally keep them just in glass jars in the fridge. In the North, they usually dry them. They take to the slurry. I smear it on the baking parchment, put it in the open, and get these hard thin chips that they put in the freezer. But other places they do other things. Like in Lithuania, they put it in a jar and then lower the jar in the well because the temperature there is pretty stable. The Russians seem to mix it with flour so it was semi-dry basically.

Colter Wilson: It still doesn’t get contaminated right?

Lars Garshol: Well, the Russian one was contaminated, but it made good beer. So the thing, the thing unless the flour has been been treated to be sterilized, which I don’t think this was. Then there’s going to be other microorganisms there that you add to your yeast. So it’s kind of strange that they do that, but apparently it works.

Doing a deeper dive into Historic Brewing

There are so many historic brewing techniques and this blog post is only scratching the surface. I would say if you are interested in diving more into our discussion listen to our full episode. We talk a bit more about the different styles and do comparisons between modern and farmhouse methods. I would also recommend reading the Lars Blog. As it is a good log of Lars’s many adventures into farmhouse methods. Last, you should read his book as I just got my hands on it but it has very detailed information, recipes, and techniques. So far it is a very good read.