A recipe for an award winning English barleywine aged in gin barrels

An Opportunity

In March of 2015 I received a group email from my friend Todd, he was trying to put together a group buy for some 15 gallon barrels. Only there was a slight twist: these barrels were oak casks that had gin resting in them. To date, I’d only ever tried a Double IPA (DIPA) in a gin barrel, but I had fond memories of that beer, so I jumped at the chance to purchase my own barrel. The barrel came from a local distillery, Roundhouse Spirits in Boulder, Colorado. They’ve since changed their name to Vapor and their barrel aged gin to “Ginskey.”

Marrying Barrel to Base

DIPA was a natural fit for the barrel. After all I had experienced a good gin-enhanced DIPA before, so I knew it could work. But IPAs tend to age so poorly, and I’d likely need to make a more caramel heavy, almost American barleywine base in order to ensure the aged beer that came out of the barrel did not fare poorly. I considered an American barleywine, and dry hopping it post-barrel to add some fresh hop presence in the finished product. But this hop-forward style wouldn’t likely age particularly well, and I was unlikely to go through the batch in the first year. I wanted a beer that would still taste good during years 2, 3 and 4.

A doppelbock was also briefly considered. The maltiness of that beer could go really well with the spirit and its botanicals. But doppelbocks aren’t usually large enough to stand up well to barrel aging. Barrels tend to thin a beer out. And it would be difficult to appropriately hop a doppelbock for barrel aging, to not have it come out a sweet, thin mess.

So I cast my eye towards something a bit larger, a bit heavier. Yet an imperial stout would not do; the roasted malts are too likely to clash with the sharp juniper-heavy botanical flavors of the gin. I considered a big Belgian tripel , and while there is risk between the sharp yeast flavors and the gin flavors clashing, it could’ve worked well. But after considering all those styles, an English barleywine seemed like the obvious pick. It has the body to stand up to a barrel, the flavor to work well with, but not outshine the gin, and it is one of the best styles of beer to age.

Recipe Formulation

My prior English barleywines were usually 100% base malt (Maris Otter or Golden Promise), modeled after the old dusty bottles of JW Lees or Thomas Hardy’s that I’d find neglected on the shelves of local liquor stores in the Chicago area. They usually featured a single hop (Kent Goldings were always a favorite of mine) and they took several years to really come into their own.

But for this beer, I didn’t want to wait several years. I wanted to enjoy it within the first year. I had good experiences brewing Belgian quadrupels that could taste really good when young by adding some crystal and dark malt complexity to the grain bill. And Belgian quadrupels are basically the Belgian equivalent to English barleywine, so I scoured some of my brewing books for inspiration and got to work on a recipe. The closest recipe to this one is probably Gordon Strong’s Draft Dodger on page 3 of his Brewing Better Beer book. While the base malt and hopping is different, the influence of his supporting malts is obvious when you compare the recipes. It’s designed to drink with good complexity within a year of brew day. And while it should age well for years to come, with less than 40 IBUs, my recipe was always destined to become quite sweet after a couple of years of hop degradation.

The barrel, which is an ingredient in this recipe in its own right, is only 15 gallons. That means the ratio of surface area in contact with the beer to volume is large. The flavors of the barrel will incorporate themselves into the beer faster compared to a traditional 53 gallon bourbon barrel or 60 gallon wine barrel. I planned for about 6 months of barrel aging with this beer, but these things are always best done by taste, so we started tasting samples at month 4. The beer eventually came out of the barrel after 8 months.

Partnership

I partnered up with Nathan, my usual brewing buddy, to brew this beer. We often made big beers together and were used to splitting 5 gallon batches. Neither of us really wanted 7.5 gallons each, so we brought in Adam, my friend, to take a one-third share.

Mistakes Were Made

One of my cardinal rules of barrel aging on a homebrew scale is to always have the liquid fermented and ready to transfer into the barrel when you purchase the barrel. I did not have this rule in 2015, and violated it routinely back then. I’ve often tried to mimic what larger, well reputed breweries do and some of the best clean barrel programs in the world routinely violate this rule. But they also have far better sanitation procedures, testing capabilities and other safeguards (and they still dump plenty of beer that goes bad in the barrel!).

The other mistake that I made with this batch was not adding a bottling yeast when we bottle conditioned this beer. We figured enough residual yeast was still left in the beer, since we didn’t filter it. But the combination of a 13.5%+ ABV beer and 8+ months after the yeast pitched meant that there wasn’t anything left that could carbonate the sugar that we added to the batch. In hindsight, this was a silly mistake, but I hadn’t bottle conditioned many big beers to this point.

Somehow, both mistakes did not burn us. The barrel/beer never soured, no wild yeast contaminated the batch. However, when we checked the beer two months after bottling, it had absolutely zero carbonation. We were able to recover by adding a few granules of fresh Fermentis S-04 active dry yeast (the primary fermentaion strain) to each bottle and recapping with fresh caps. (A bottling strain like Lalbrew CBC-1 or Fermentis EC-1118 would have done too.) Roughly six weeks later, the bottles were carbonated. Crisis averted!

Flavors and Medals

When we primed the beers for refermentation, Adam didn’t want his share carbonated because he enjoyed it as-is, still. He’d grown accustomed to little to no carbonation and higher beer serving temperatures during his time living in the UK and drinking cask ales. So he drank uncarbed 13.5% barleywine at room temperature (ironically he also went through his share within 6 months!).

The flavors in the final beer were delicious. It was initially juniper-heavy, but also had some great vanilla depth from the oak barrel. It was all held together by some thick caramel, dark fruit and bready toast flavors from the malt. It was decadent, but not too sweet.

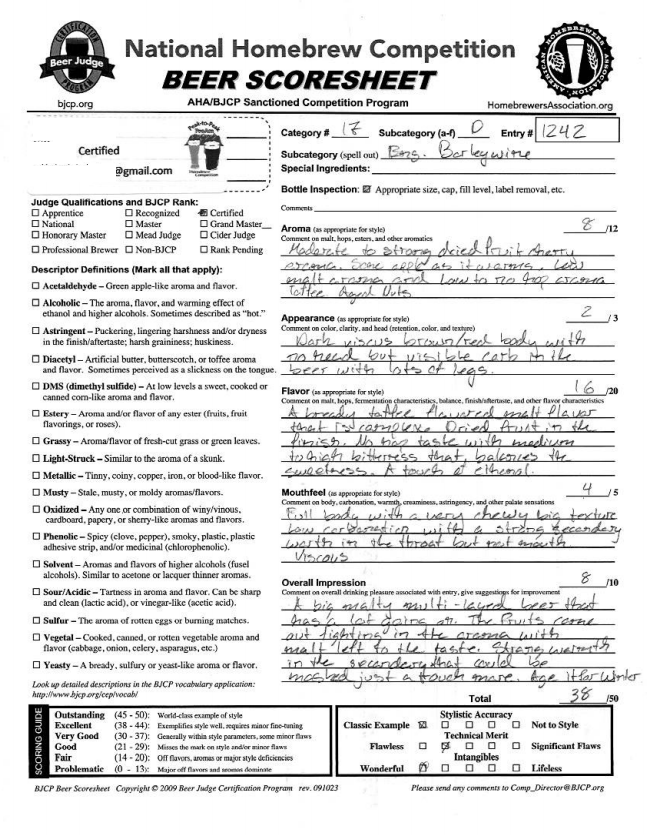

We entered the beer into three different competitions, all in the specialty wood category, when it was anywhere from 10-24 months old. The beer was entered into the 2016 Peak to Peak Pro-AM and received 3rd place with a 39 consensus score. At the 2017 Big Beers, Begians and Barleywines Festival in Breckenridge, Colorado, we won a silver medal for this beer. It also scored a 36 at the NHC, but did not move on to the next round.

Comments from the scorecards included descriptors like “caramelized sugar, heavy bread, intense toffee, dark fruit, clover honey, moderate vanilla, molasses on the nose, spicy flavor, thick and syrupy without being too heavy, vanilla from the wood, subtle juniper. Rich, bready, complex flavor, black raison, prune, smooth, intense alcohol, sweet, nutty finish.”

Brewing this Beer

If you want to brew this beer, the toughest part will be acquiring a gin barrel. While craft distilleries have really blown up in the last five years, it’s still rare to see barrel-aged gin. It’s even rarer to find a 10-15 gallon barrel. If you do find a full sized, 53 gallon barrel, expect to age it 10-15 months to replicate the flavors that we did in this beer in eight months. With a 10 gallon barrel, I’d start to check it at month 4, and with a 15 gallon barrel start to check around month 5. Always barrel age to taste, once it’s ready, take it out and package it.

If you cannot find a gin barrel, you can work on substituting with medium toasted oak (spirals work great here) or some charred oak chips. If you char oak chips yourself, make sure to leach out the excess astringency by boiling them in water for 10 minutes before using them. I’d then add 4-8 oz of gin per five gallons of beer to your final beer. I’d pick out a gin that has some good botanical flavor. Gin flavors can vary widely. Go to your local distillery(ies) and check out what is available. If you happen to find a barrel aged gin, you could just use that, and skip the wood, since the gin will inherently have flavors of wood. (You can always add chips to taste if the initial BA gin doesn’t give you enough of the wood component.)

On the packaging front, I know we bottle conditioned it so that it could develop over time, but after a few years it got pretty sweet. It was still nice, but I don’t think it was worth the trouble of reconditioning on yeast in the hopes that it would continue to evolve for many years to come. If I brewed this again (unfortunately for me, the distillery now only uses 53 gallon barrels for the gin), I would force carbonate in kegs and bottle it up. It will still mature and taste great for years to come. I think this beer peaked between years 2 and 3, and still tasted good until at least year 5. It has gotten quite sweet (I still have two bottles that I stashed away), but that’s not uncommon at all for an English barleywine.

If you’re looking for something that might not peak until years 3-6, or something that will continue to develop and change for many years to come, consider increasing the bittering hops to 50-60 IBUs and recondition at bottling like we did.

I listed the specific malts that we used in the recipe below. Using malts from other maltsters or using similar malts (e.g. 60L instead of Simpson’s Medium) is totally fine. Substituting hops would be fine too. Magnum or Target would work well as the bittering addition. Fuggles are a suitable hop for flavor. You can explore a bit wider too. The point of the beer is not to have much hop flavor, the hops are primarily there to bitter and balance the big sweet malt flavor.

Fermentis S-04 is what we used and it worked well, but any English yeast capable of fermenting upwards of 13% ABV would work well. White Labs WLP099 Super High Gravity is reportedly the Thomas Hardy’s Ale strain. I’ve used that in other barleywines and in stouts with great success. Make sure to pitch a large amount of healthy yeast. Use the Brewer’s Friend Calculator for pitch rates if you’re unsure.

King Juniper

Recipe Details

Batch Size |

Boil Time |

IBU |

SRM |

Est. OG |

Est. FG |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5 gal |

60 min |

38.9 IBUs |

25.4 SRM |

1.128 |

1.029 |

13.3 % |

Style Details

Name |

Cat. |

OG Range |

FG Range |

IBU |

SRM |

Carb |

ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

17 D |

1.08 - 1.12 |

1.018 - 1.03 |

35 - 70 |

8 - 22 |

1.6 - 2.6 |

8 - 12 % |

Fermentables

Name |

Amount |

% |

|---|---|---|

Pale Malt, Maris Otter (Thomas Fawcett) |

17 lbs |

64.64 |

Crystal, Light (Simpsons) |

2.25 lbs |

8.56 |

Amber Malt (Bairds) |

1.5 lbs |

5.7 |

Biscuit (Dingemans) |

1.5 lbs |

5.7 |

Wheat Malt, Pale (Weyermann) |

1.5 lbs |

5.7 |

Dextrin Malt (Simpsons) |

1.25 lbs |

4.75 |

Crystal, Medium (Simpsons) |

8 oz |

1.9 |

Turbinado |

12.8 oz |

3.04 |

Hops

Name |

Amount |

Time |

Use |

Form |

Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Challenger |

2.25 oz |

60 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

7.8 |

East Kent Goldings (EKG) |

1 oz |

5 min |

Boil |

Pellet |

5 |

Yeast

Name |

Lab |

Attenuation |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

SafAle English Ale (S-04) |

DCL/Fermentis |

73% |

59°F - 75.2°F |

Mash

Step |

Temperature |

Time |

|---|---|---|

Mash In |

152°F |

75 min |

Fermentation

Step |

Time |

Temperature |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

14 days |

67°F |

Secondary |

14 days |

69°F |

Aging |

5 days |

33°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |